In action

Before daylight on 3rd January 1941 came a hot breakfast and, surprise surprise, a tot of rum each to keep out the cold and steady the nerves. I have to admit that it did help. As a non-drinker it helped me more than some of the others. Powerful stuff, Army Rum. A tot of rum before a battle has been an army tradition for generations.

The attack on Bardia had begun. As day broke we moved north-west from our positions until we were opposite the gap that had been driven through the enemy's outer defences by the first wave of our troops. They had attacked while it was still dark. I confess that I was feeling very nervous. We all were. The noise of artillery fire from both our guns and theirs was intense. Our artillery had started rapid fire just before dawn, an hour before we had to move and the horizon on both sides was lit by an almost constant flash of the guns. With the noise of our artillery and the continual bursting of enemy shells replying, everyone was feeling more excited and edgy as the time came to start the advance. To give some idea of the artillery activity, our troops were firing almost one hundred guns of various types. We found it of interest to identify the various guns by their sound. One found it better to dwell on other things rather our future activities.

We eventually captured four hundred and sixty Italian guns including their anti-tank guns most of which were combined anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns. Only a switch of ammunition was necessary to change roles. With all these guns firing as fast as they could, there is little wonder that there was a lot of dust and noise about.

We could not be blamed for being a bit nervous as we waited. Once started our movement had to be across open ground. No sheltering in slit trenches from now on. The enemy artillery sent some shells over our heads onto the transport of our heavy artillery unit. One truck was soon blazing and I am sure that others must have been damaged. No doubt the continuous firing of the guns enabled the enemy observers to get the range and position. Those shells landing in amongst our artillery were very large, much larger than what we had encountered previously. The enemy must have been saving them for a special occasion. They made a sound like an electric train as they passed overhead.

Everyone seemed to have frequent cause to stop for a nervous wee, a problem that passed as we settled down and actually started to do something constructive. We were advancing in open formation which meant that we kept about ten paces apart until we reached the enemy wire. We started with fixed bayonets. They would not be needed for some time but the sight of them glinting in the early morning sunshine gave us a boost and hopefully would help terrify the enemy. We moved forward over high ground then into the hollow in which lay the gaps in the wire. The barbed wire entanglements had been breached just before dawn to enable the first wave of our troops to pass through to attack the nearby defence posts. The gaps in the wire were made by our Engineers using devices called Bangalore Torpedos. This Australian invention consisted of a length of 2 inch diameter water pipe filled with high explosives. It was pushed under the wire and when exploded it cut the wires above it. Once again when the series of explosions occurred, the enemy fired their anti-aircraft guns, thinking that it was an air raid.

AIF troops advance to Bardia

As we topped the rise overlooking the gap in the wire we had our first close look at the enemy defences in daylight. Concrete defences and barbed wire were plainly visible. Our advance onto the skyline gave the enemy gunners a good view of us, their target. The shell-fire became heavier and more accurate with shells bursting all around us. One hit the ground no more than two feet from me and bounced away without exploding which obviously saved my life. In any barrage they fired we noted that at least one, and sometimes two, out of ten failed to explode. I was grateful that the percentage worked my way that time.

As I reached the enemy wire and was about to go through, I looked back to where the last of our Company were topping the rise that I had just crossed. It was like a scene from a war movie with our chaps advancing through a pall of smoke and dust, shells bursting amongst them and the sun glinting on their fixed bayonets. Some men were going down but amazingly getting up again and moving on, all the time maintaining their line and spacing. I felt proud to be part of it. It was an inspiring sight to me but must have been frightening to the watching enemy whose morale was already shaken by Mussolini's propaganda when he referred to us as "bearded animals living on an onion a day and taking no prisoners". As some of our boys said, we wished that the part about the onions had been correct. Onions would have helped make the bully beef more palatable.

There were three bodies lying outside the first post on our left as we crossed the anti-tank trench and the wire. They were inside the encircling barbed wire of the post and had obviously been killed by a heavy explosion as their bodies were so stripped of clothing as to be unidentifiable as being ours or theirs. There was a lot of blood and wounds visible. I would like to believe that they were enemy soldiers. I didn't want to see our chaps in that condition. Captain Green had a long look at them through his binoculars then turned to me with the offer of a look. He was that sort of officer. While I was looking I am certain that I saw one of them move his arm. I turned to tell the Captain but by this time he was about twenty yards (19m) away and going at his usual rapid pace. By the time I caught up to return the glasses there was no point in saying anything. I have often wondered whether the unfortunate person survived. After crossing through the wire entanglements we wheeled right and followed along betwben the two lines of posts already captured. We were still maintaining wide spacing.

Since leaving the gap in the wire we were in a hollow and out of sight of any enemy positions. There were no machine guns firing at us and only an occasional shell landing. We had thankfully reached a quiet area. There was plenty of evidence of heavy fighting and other casualties as in most cases when the stretcher bearers carried away a wounded man, his equipment was left lying where he had fallen, to be retrieved later. There were several sets of equipment lying about near the posts that we were passing. At that stage enemy dead were left where they fell until later. There were very few enemy dead as our side was copping most of the casualties being the ones moving across the open ground. Enemy wounded were treated the same as our own. Enemy medical personnel were being used to augment our very busy Medicos who were already setting up a Field Hospital inside the wire. They had some Italian doctors employed. They were treating wounded from both sides.

Now that we were out of sight of the enemy most of us unfixed our bayonets. The rifles feel different when being carried with bayonets fixed. Most men prefer to move without them especially when getting up and down. The extra weight on the end of the barrel made shooting less accurate.

A sad spectacle was a young lad from one of the first battalions through, he was crying as he nursed the head of a wounded soldier. He said that it was his brother. I stopped to set a signal for the Stretcher-bearers. This is done by driving the bayonet with rifle attached, into the ground. The reversed rifle is the signal for a man needing help. I was pretty sure that the wounded boy was dead but hadn't the heart to say so. The members of the Battalion Band, when the Unit went into action, lay down their instruments and became stretcher bearers. They naturally received First Aid training.

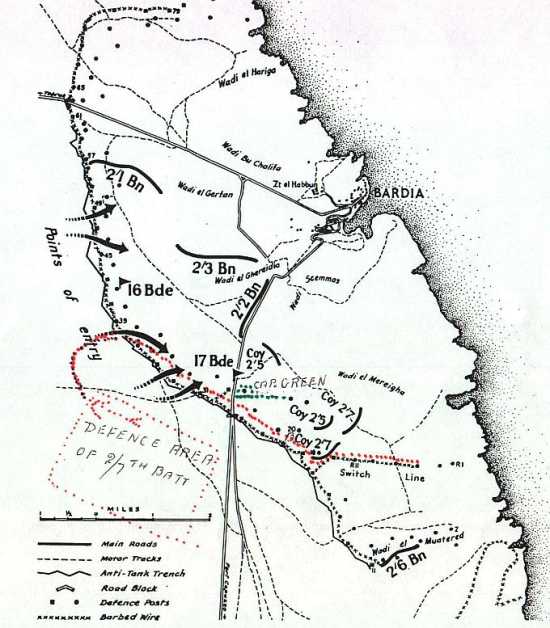

"B" Company was to take up a position along the Bardia to Fort Capuzzo road which ran at right angles to our intended direction of advance. At the appointed time we would take over the attack along the outer defence line capturing posts in turn. There was also, an inner line about 400 yards (375 metres) behind the outer defence line giving them cover. Our attack had to capture both lines. After capturing a number of posts B Company was to follow a switch line which was protected by the same obstacles as the outer defence posts. (see map). Since passing through the wire we had been moving over land that rose slightly until we reached the highest point along the front. To our left there came into view a wonderful sight. Wonderful that is to an attacking army. About half a a mile away was a long line of captured enemy troops moving back towards our rear. There were hundreds of them. It gave us quite a boost to see so much evidence of our success so early in the fighting.

As we reached the higher ground we once again came under observation of an enemy artillery observer who reacted by bringing down a considerable barrage of shellfire. We continued on down into a lower area to where it was reasonably sheltered. Our jumping off point was to be the Bardia to Fort Cappuzzo road. As we waited for the time to begin the attack, the embankment where the road crossed a large shallow wadi and the cuttings on each side gave good cover to our first line of troops consisting of two platoons. The rest of the Company were lying on higher ground behind us and in the open without any shelter. They were under observation by an enemy artillery observer nearby. We could only guess at that fact at that stage because the artillery fire was so heavy and accurate with shells and shrapnel bursting among them.

As I was runner to our Company Commander Captain Green, he sent me and a nearby man, Stan Phillips to tell the Platoon Commander on the higher ground to move his troops back to a safer site to avoid casualties. Sending two men with the same message was for obvious reasons. How dangerous it was up there was shown by the fact that Stan returned with a shrapnel cut in the butt of his rifle and my rifle sling was almost severed either by shrapnel or a bullet. The enemy was not only using the usual high explosive shells but a type from World War 1 which was a shrapnel shell that exploded low overhead and sprayed the ground with halfinch diameter pellets like an over-sized shot gun. As the shells burst they left a cloud of coloured smoke. This, no doubt enabled the directing officer to direct individual guns, assuming that each gun used a different colour.

When I reported back to Captain Green he handed me his binoculars and told me to note an enemy officer about 200 yards (190m) ahead and to one side. This man was watching the shelling of our chaps through binoculars and directing the artillery that was causing the trouble. He was a small target only partly in view from the thighs up. There was one of the previously mentioned poles a few feet from him. He was evidently standing on the steps leading down to the bomb-proof shelter. I took careful aim with my rifle resting on the edge of the road. I fired and for a second lost him in the flash of dust caused by my rifle blast. Then it was clear he was no longer there. This was the first shot that I had fired at the enemy, my first live target and I had killed or seriously wounded a man. I knew as I squeezed the trigger that I was spot on. Possibly the first enemy hit by one of our Company, probably the first for our Battalion.

Had I taken time to think about it, I may have missed. As it was I was sobered by the incident and never did discuss it with anyone. I certainly got no thrill from it, although there was a sense of satisfaction at hitting a difficult target. I put the incident out of my mind and only spoke of it to Shirley some 49 years later. I perhaps never will be entirely comfortable with the fact of wounding or killing that human being who happened to be on the other side in this conflict. At the time he was unarmed and defenceless with both hands up to his eyes, holding his binoculars. Firing on an enemy attacking you or fighting back is an entirely different matter. My mates were saved from further heavy attack but the bare facts of the matter still remain. Only Captain Green and myself were aware of the episode. The enemy artillery fired a few more rounds but soon became inaccurate and, no doubt started to fire on other targets controlled by other observers. After I fired, Captain Green congratulated me for a fine shot. He had been watching through his binoculars.

Soon afterwards an enemy soldier ran down the side of the Wadi partly towards us heading for an opening at the foot of the slope. A couple of shots were fired at him but immediately several voices were raised telling them to leave him alone as he was unarmed and was not doing any harm. It was rather surprising to see a sense of mercy and fair play existing even in wartime and in the heat of battle. I would wager that had the position been reversed and one of us was running across the front of their lines there would have been no call to hold fire.

At about 0900 hours (9am) the order to advance came. We fixed bayonets and off we went wondering what would happen once we topped the rise ahead where the first of the enemy posts were situated. We were to follow a barrage of our artillery which was to creep slowly ahead of us, the theory being that the enemy would be knocked out and easy for us to capture. It did not work out that way as the enemy were in bomb proof shelters. As soon as our barrage had passed, they emerged, firing on us from fairly close range and from at least two directions at once. Not only that, but some of our shells landed on rock and the shrapnel flew amongst us. It was plain to see that our 25 pounder shells were much more powerful than those used by the Italians. Things were very hot and I cold not see how on Earth we would survive much less capture those fortified posts. Their artillery was firing on us and the machine guns in the two posts were firing continuously so that our boys were forced to advance slowly by "leap frogging", one section lying down firing while another rushed forward a short distance to one side before going down to fire also. As I was lying low at one stage a piece of shrapnel bounced off my hat. It made a slight dent and a scrape mark in the paint. Our artillery fire meanwhile moved slowly into the distance. That was the last support we received from them.

The post on our left, which had neither barbed wire entanglements nor a tank trap, was the first to surrender, raising white flags. It amazed us to see that most of the troops surrendering seemed to each have a square of white cloth. As some of our boys suggested, they must have been Army Issue, for just such an occasion. While the enemy troops were being brought out of the post with their hands raised, Captain Green started walking forward with me about five yards behind him. When he was only about 25 yards from the group of prisoners an Italian soldier climbing the steps raised a rifle and shot Captain Green. I saw the man raising his rifle and tried to get my rifle off my shoulder and into a firing position but I was too late. The shot went through Captain Green's respirator canister and into his solar plexus. He was knocked over backwards onto the ground and did not move. It was so maddening, I saw it happening yet could not do anything to prevent it as I was carrying my rifle in the slung position and the incident only took a couple of seconds. Several of our men fired but too late to save our Captain. After he fell we tried to help, even making an enemy Medico try but all we could do was dress the wound in his stomach. There was a lot of charcoal in and around the wound but not much bleeding.

When Captain Green fell the nearby Platoon Officer sent me to inform Lieutenant MacFarlane that he (Wadi Mac) was now Company Commander. By the time we returned together Captain Green had been taken away by stretcher bearers. We later heard that he had died without regaining consciousness. While Mr. MacFarlane was discussing the situation with the officer, Mr Davis, two runners arrived from the other platoons with the grim news that both of their officers had been wounded. Within an hour Lieutenant Davis was also wounded. None of them wounded fatally but all were unfit for further active service. I believe that all three were wounded by shell fire. Captain Green was a very capable and popular commander and his death was a blow to us all. It hardened our attitudes towards the enemy. I find it hard to understand a soldier virtually committing suicide by killing someone in that manner. The shots fired by our chaps at the killer caused several other enemy to be also hit. They had been bunched up fairly close together as they climbed the steps out of the post. The shooter was almost in the middle of them. The man who fired that fatal shot while under the protection of a white flag forfeited the right to be treated as a prisoner.

Many years later in Morwell, Victoria, I was visiting the Morwell Private Hospital where my daughter Elaine had recently given birth to her first child. Passing along a passage I saw a plaque on the door of a ward, commemorating the life and death of Captain Green. It was placed there by his wife and family. I could not resist a look inside. I don't know what I expected to see but it gave me a turn to find a room full of local Italians happily chatting with a lady in the bed. There was no reason why they should not be there. Yet somehow it seemed to put me off balance.

I have always regarded Captain Green's death as a murder. Suddenly seeing the plaque had caught me off guard, then seeing the Italians so happy there brought it all back. Maybe the problem lies in the fact that in war time one does not get the chance to say farewell to a friend. He goes down and you move on. I still wish I could have said a last 'Goodbye". If not to "The Skipper" to his face, then by his graveside. A funeral closes the book. I now realise that the book will never be closed for me. I also believe that this is probably why people grieve for so long for their war dead. The separation and the loss are compounded by the lack of a final goodbye and the lack of a funeral or a grave. No doubt it has something to do with the desire of old soldiers to go back to where fallen comrades lie - for people to go to great expense to visit the graves overseas of loved ones even after fifty years.

"B" Company had now lost four of its five officers but carried on with sergeants and a corporal in charge of the platoons. They didn't miss a beat. Our casualties were heavy but the attack went on as before. We lost men at almost every post we took, two men being killed when a shell burst between them while they were moving too closely together. We had the company of a heavy Infantry Support Tank for an hour or so which really made life a lot easier. I think that tank was known as a "Matilda", very heavily armoured and quite slow, equipped with a two pounder anti-tank gun and a machine gun in its turret. The enemy quickly raised their white flags once "Matilda" got into position and fired into the post. We did not blame them.

Matilda tank

On one occasion the new C.O., Wadi Mac, saw that one platoon on the right was having a heap of trouble. He sent me with a message to the sergeant in charge to withhold their attack until the tank could be moved over to assist them. After delivering the message I was on the return trip when I saw a man struggling on the ground and went to his aid. He was an engineer attached to "B" Company to do any demolition jobs that may be necessary. He was wounded and bleeding a lot. As he seemed anxious to be rid of his equipment I helped him out of it, placed his haversack and webbing nearby. He said that it was not good enough but to find a shell hole to put them in as the haversack was full of high explosives and detonators. Fancy wandering around a battle field with that on your back. He had been wounded in the groin area by shrapnel when a shell burst close in front of him. With my limited knowledge of First Aid I seemed unable to stem his bleeding. So I set a signal for the stretcher bearers and First Aiders and stayed with him until they arrived. I think that he would have survived as the bleeding did not indicate an artery involved.

There was a lot of shell fire falling around us at that time and a machine gun somewhere a long way off had us in his sights. Either the range was too great or he was a lousy shot because neither of us was hit although bullets used to whip up bursts of sand near us from time to time. On arriving back with the Headquarters group it was to find that a lucky shot from an artillery shell had blown one track off the tank. The broken track lay stretched out on the ground behind the tank showing that the tank had just driven off the end of it before becoming bogged in the sand. As the track weighed over one tonne and the tank weighed about thirty tonnes, the crew had no facilities to make repairs of the kind required. We received no further help from them. I saw where an enemy anti-tank projectile had struck the tank on the turret. It had failed to penetrate the thick steel of the turret and had merely made a deep powder burns around it. The crew said that when it was like having ones head in a bass drum while it beaten.

At around mid-afternoon we came upon a post different in appearance from the ones seen to date. Set on a rise and a bit back from the others of the rear line and it was poorly defended. When we ordered the occupants out we discovered that we had captured a Divisional Headquarters complete with a General and other top ranking officers. They all emerged trying to look dignified and haughty. One would have thought that they were the victors and not the vanquished. Their attitude plus the fancy clothes they were wearing did not go down too well with the Aussie troops. The larrikin of our company who was acting runner to Wadi Mac piped up "What rank is this bird, Mister Mac?". On being told that the man was some kind of General our lad walked up and gave the said General a swift kick on the tail. Mr. Mac berated him for his action and pointed out that enemy officers when prisoners were entitled to the same treatment as our own officers. The kicker replied, "I'm sorry Mr. Mac but I have often felt like kicking the backside of some of our officers. Meeting a General was too much to resist." The man's name was Bill (Boots) Jinnette. He was awarded a Military Medal for actions at Bardia, but not for his actions with the General I wouldn't expect.

Our attacks were successful. We captured a lot of prisoners until late in the day. We came to a post which had the natural advantages of being sited on the edge of a deep wadi. It had usual defences of an anti-tank ditch and lots of barbed wire. As their firepower was too heavy for us to get near in daylight, it was decided that it would be taken after dark. When it was fully dark one of our sections crept up along the wadi and cut the wire. Several men were inside and had moved around to one side before the enemy discovered their presence. There were always at least 20 strands of wire to be cut to cause a gap large enough for a man to get through. Cutting that wire within twenty paces of the enemy sentries was real nerve-tingling stuff. Once discovered all hell broke loose with both sides throwing grenades, firing rifles and machine guns. To add to the difficulties, some of our troops had difficulty finding the opening cut in the wire. Brian Fogarty, the man who was to guide them through the gap, was wounded and lay unconscious. Several men were wounded but only two badly, Brian Fogarty and Les Angus, the latter with a bullet through his tin hat and his head as well. He was alive and conscious as the Stretcher Bearers took him away. Portion of his brain was visible but he survived.

Before the attack started I was attached to a section that was sent around to the right on the outside of the wire in an attempt to fire on the post from the side. When we arrived we were not able to get a clear shot owing to slightly rising ground between us and the enemy position. We discovered that some of our men had moved around inside the wire to a point approximately opposite our position. We had to hold our fire, but at least we had a ringside seat to the fireworks. The Italians were throwing hand grenades every couple of seconds. These exploded with an extremely loud bang and a bright flash that momentarily lit up the scene. Our chaps were more sparing with their grenades mostly because they only carried two each. When they did throw one it exploded with a heavy crunch and sprayed shrapnel for yards. Italian grenades were light metal affairs and contained small shot, the size of bird shot which many of our chaps scorned as kids stuff. Later it was found that some of them had been hit by this fine lead shot that caused troubles requiring hospitalising.

Bardia assault

There was a great deal of machine gun and rifle fire flying in all directions. Between the grenade bursts the darkness seemed to be more intensified. The defenders were, I think, bolstering their courage by blazing away regardless of whether they could see a target or not. Being the defending force the enemy had oodles of ammunition to expend while we had only what we could carry. The defenders of the post were eventually subdued and taken away. We were able to get some sleep during the remaining few hours of darkness.

Next morning it was on again. We had a couple of successes before we met another tough one. This post was sited on top of a slight rise. It was completely surrounded by the usual barbed wire entanglements plus an anti-tank ditch inside the wire completely encircling the post. This post covered a larger area than usual and the anti-tank ditch was covered with boards and camouflaged. The troops inside the post showed a spirit and determination not shown very often elsewhere. Another post only a few hundred yards away was also chipping in with machine gun fire. it amazed me that we were able to capture the place at all. It was mid-afternoon before the white flags were raised. The dust had hardly settled, the prisoners rounded up when an enemy 75 mm artillery piece opened up from about 700 yards away, ignoring the fact that about 80 of their troops were standing amongst our troops. There were considerably more Italians than Australians in the group. By this time our numbers were down to at the most, half that with which we set out on the previous morning. Up to this time our losses had been pretty heavy. Fortunately that first shot was a little high and went straight through the group without hitting anyone or anything, exploding well away. Everyone dived for cover and had to stay there until dark with the artillery slamming shells every few minutes. As well, at any sign of movement the machine guns of the next post would sweep the area.

While the prisoners were being searched for weapons etc. I had moved out through the gap in the wire with a couple of others to control the prisoners as they emerged. When the first shell screamed through the group everyone dived for cover but we three outside were caught in the open without cover and no chance of getting back inside with the others. At first we were concerned but then realised that as we could not see the gun it could not hit us. The post was sited on top of a rise, the gun was on the next slope at a slightly lower level. At close range a shell travelled in almost a straight line. It is only after a distance that the shell's trajectory begins to curve downwards. So, keeping low, we retreated to the relative safety of the wadi from which the assault had been launched. The prisoners were directed into the tank trap and our chaps took cover in the bomb-proof post. In spite of the gun shelling our men at point-blank range for the rest of the day and machine guns sweeping the area they were reasonably safe so long as they kept their heads down.

Sergeant Joe Solomon from Darnum put his head up to fire back at the enemy just as they fired a burst from their machine-gun. Joe fell with a bullet through his head and died instantly. Everyone kept low after that. I had known Joe since the Militia days. It was only a couple of weeks before we left Ikingi Marouk that he received his third stripe (became a sergeant). He was however only made an acting sergeant which, while giving him the power and responsibility of his three stripes, left him with the pay of a corporal. What with celebrating his promotion and other expenses of the Sergeant's Mess, He soon ran up a large account. When the time came for the unit to move into action Joe received a bill that he had no chance of covering. He came to me in a panic and borrowed five pounds or three weeks pay. It was bad luck, Joe lost his life and I lost five pounds. I would of course been happy to lose a lot more than that to see Joe back again.

During the daylight hours the enemy machine guns would have been set in fixed positions on tripods so that after dark all they had to do to sweep the target area was pull the trigger and know that their bullets would spray the target. We never knew when another burst of fire would come our way.

One member of our company was Corporal Jock Taylor, a raw-boned six feet tall Scotsman with red hair,previously mentioned as being at Puckapunyal. He was a character who always stood out in a crowd and was popular and dynamic whatever was going on. While outside Bardia he had disgraced himself by telling an officer a few details of his, the officers, parentage. The result was that an understanding Colonel Walker removed him from our Company, gave him the task of recording the fall of enemy shells in the Battalion area of operation during the attack. If the Colonel had not been sympathetic Jock would probably have lost his stripes and gone to gaol. As Jock recorded the number of shells that were falling on "B" Company he began to get very restless until he could stand it no longer. He went to the Colonel and pleaded that the boys needed him desperately and to please let him go. At last his pleading bore fruit. Soon afterwards we saw a smiling Jock striding towards us. As he reached the edge of the post the people inside called to him to duck his head to which he replied that he would never bow his head to any Italian soldier. It was not just bravado, he meant it.

As soon as it was dark, four of us went for rations. We were very popular when we arrived with bully beef and biscuits and two 4 gallon dixies of hot tea. I carried the tin of biscuits. It was a little over two feet square. As soon as I set out from the wadi I knew I had a problem. The tin seemed to be shiny and I was sure that it would be visible for a mile in the starlight. The worst part was, the tin bonked loudly at every step. It was really not very shiny at all as it was as usual, sprayed with a type of brown varnish but to me it seemed to fairly glitter. I returned to the wadi and scrounged a blanket in which I firmly wrapped the tin. It didn't completely stop the bonks but at least it muffled them somewhat.

After doing that I realised that I had lost contact with the others. In the stress of the moment I feared that I may have lost my sense of direction. I moved in what I hoped was the right direction for about four hundred yards which I knew was the approximate distance to our Company. It was also the distance to the enemy occupied post, if my directions were badly wrong - !! I eventually reached some barbed wire entanglements but, in the dark, was at a loss to tell where I was. I knew that I had found an occupied post, but which one? To put it very plainly, I was lost in "No Mans Land". I crouched down against the wire hoping to see someone against the skyline, identifying them as friend or foe. They would have been only about twenty five yards away. Suddenly there was a burst of machine gun fire from a distance and almost behind me. A couple of bullets twanged the wire over my head. I knew then that I had reached the right spot, soon found the gap in the wire and thankfully delivered my burden.

Once rid of my tin I lay on the bank on the side of the post away from the enemy fire and talked to some of the men inside. I noticed someone lying alongside me and spoke to him. He didn't answer me. He was a dead enemy soldier who had been put out of the post. Having been dead for a couple of days he was getting smelly. As I was still a runner without an officer to run for, I decided to return to the wadi and spend the rest of the night with Company Head Quarters. It took me quite a while to get to sleep. I am afraid that I slept badly as for the first time in my life, I was troubled by recurring dreams of danger. Next morning I searched dugouts lining the Wadi and found a dead soldier in one with a dead Artillery Officer nearby. I heard a sound from one dugout and called for whoever was inside to come out with their hands up, at the same time covering the entrance with my rifle. A very badly wounded enemy soldier slowly emerged. He was quickly taken away to hospital. All the other dugouts appeared empty. These dugouts were caves consisting of a room about ten feet square that the Italians had dug into the banks of the wadi. Being underground with some ten to twenty feet of earth for a roof they were a good idea. They would have been much more comfortable than inside those concrete posts.

A few days before the attack was launched we were given a brief lesson in speaking Italian. We were taught to say "put your hands up" and "open your hands", in Italian. The latter in case an enemy was concealing a grenade on his closed fist. What some of the men said would have been indecipherable to a native Italian, especially when the words were interspersed with strong Australian expletives. However, our meaning, reinforced by a gesture with the rifle and bayonet was quite plain and easily understood.

With the daylight came the renewal of the shelling. As most of the Company were still marooned in the post, I went up to the top of the rise some distance around to the left from the post in an attempt to discourage the enemy artillery gunners on the next rise. This gun was actually situated slightly lower than the post in which our chaps were marooned. Any shots that missed or bounced away without exploding went a mile or two before hitting the ground. Several of them landed uncomfortably close to Battalion Headquarters. I was joined by three others and we fired with our rifles at the 75 mm. gun crew. To fire in the direction of our troops in the post, the crew had been forced to move the gun out of its original dug-in site. It had been facing south, now moved to a position in the open facing almost north and away from their ammunition dugout. They had to move about ten yards to find a level place for the gun. Although the gun crew were protected by a heavy shield, the men carrying the ammunition to the gun had to run about ten yards across open ground each time the gun was fired. A moving target at 700 yards (650m) is very hard to hit. In the one and a quarter seconds it takes for a bullet to cover that distance, a man can move quite a long way, especially if he is encouraged by bullets snapping at his heels. I hit one runner and saw him fall.

This so angered the gun crew that they turned the gun around and aimed at us. We had been firing from behind a low stone wall. The first shell landed a little short of its target and hit the base of the wall a couple of feet in front of me, kicking up a great cloud of dust, sand and smoke. I actually saw the shell as a black spot against the flash of white smoke as it came straight at me. When it exploded we, without saying a word, as one rose to our feet and walked away in the dust cloud. We took cover in holes in the ground while the gun tore the wall down. At least while it was firing at where we had been, it was not firing at our men in the post. As there did not appear to be much future or benefit in continuing to tease the artillery crew we returned to the wadi. But it was fun while it lasted.

Early in the afternoon an English Major followed by a couple of chaps running out signal wire came up the wadi. He asked if we knew where "B" Company and the enemy artillery were. I was delighted to guide him to the right spot. Especially since he was the observer for the 6 inch (152mm) battery which we camped near before the attack started. The Major was very nervous and stressed that he must not be seen by the enemy. He was also nervous at being so close to where his shots were to land. He claimed that no observer was ever asked to work so dangerously close. When I overheard his instructions to the gun which was to fire the shot I understood. An error of only one degree could have landed those big shells on us. It only took four shots, each one a little closer than the last, for those enemy gunners to get the message. They deserted the gun and took off up the hill to where a truck picked them up. They disappeared over the horizon. I fancy they were in for a surprise as, for them and the rest of the Bardia garrison, the war was over. Bardia town had fallen to our forces and most of their fortified positions had been over-run. At the same time, another Company of our troops on the other side had taken the post which for so long had bothered us. Our chaps emerged from their shelter, very grateful to be able to move around in the open again. There is something very claustrophobic about being in a concrete bunker while someone is bouncing shells and bullets off it. Give me the open air every time. Watching those big shells of ours land with a mighty bang and kick up great clouds of sand and dust was very dramatic and cheered us no end. It is not often that one can get so close to the target with our big guns.

A couple of Australian soldiers with a gang of Italian prisoners were moving around the now quiet battlefield collecting enemy dead for burial. We had come through our first test and felt that we had proved something, at least to ourselves. We had lost some good friends but felt we had learned some lessons which could reduce casualties in the future. Once the fighting stopped we were still in a state of excitement and the adrenalin was still flowing. Because of the loss of so many of our officers and sergeants we were for a time left without the usual controls. Some of the men went off and got drunk on Italian wine. There was lots of wine in stores all over the place. Where we drank tea the Italians drank wine.

Most of us spent our time exploring posts and depots in our area. Others started examining various captured weapons which eventually led to us foolishly experimenting in dismantling their explosives. I helped work out how to render their hand grenades harmless. Italian grenades were percussion detonated which meant that after one had pulled out the pin, they needed to be dropped or bumped to make them explode. One had to avoid kicking any grenades lying around as a light kick was enough to set them off. We pulled the pins from a box full then repacked the box. After moving away a short distance I fired a shot from my rifle into it. We considered the resulting bang was worth the effort. This type of behaviour was repeated by others. Apart from being rather pointless it was extremely dangerous. I tell this to illustrate the kind of silly things troops do while not being properly controlled when on an emotional high. A few acts involving danger seemed to bring a type of exhilaration. I guess that, after the dangers and tension of the past few days it was a way of winding down.

There was one thing a few of us did that I think should have been included in our training. We practised at firing a Bren from the hip. I learned how I needed to lean into the gun to counteract the tendency for the recoil and to make the gun swing to one side, spraying away from the target. This knowledge enabled me later to perform better than most in trials with a Thompson sub-machine gun and thus be issued with one as we left the desert.

Australian casualties in this battle were fairly heavy, having lost 130 killed in action and 326 wounded. Our company had contributed more than its share of the losses and it came as a bit of a shock to us all. These were not just statistics that one could read in a paper. These were our friends and companions of more than a year. We deeply felt their passing. Over the next few weeks a number of the wounded returned to active duty. My special pal Bert Philp was welcomed back but still carried some shrapnel in his face, this being typical of returnees. A platoon (30 men) of the 2/6th Battalion had the heaviest losses having only two men not killed or wounded before finally capturing very well-defended post number 11.

It would have been sensible if I had described a typical Italian defence post which we found at both Bardia and Tobruk. They consisted of a series of concrete underground bombproof shelters connected by open passages and having two or three machine gun positions plus firing steps for rifle men. There was usually an anti-tank gun or an anti-aircraft gun at one end. The whole post was about 50 yards long. Most posts of the outer defence line were surrounded by an antitank ditch and enclosed by a barbed-wire barrier some 8 feet thick and 8 feet high. They were spaced about 800 yards apart with a second line some 400 yards behind. The rear line had neither barbed-wire nor a tank trap. Their role was as a support unit and were fairly easy to capture in a frontal attack. Troops pushed out of areas as far east as Mersa Matru caused these posts to be grossly overmanned. Normal manning would have been about twenty or thirty men. But due to this surplus we usually captured seventy or eighty from each.

Because of all the rock and soil dug out when building these defences, the posts were raised two or three feet (about a metre) above the surrounding desert. This gave them a good view and an excellent field of fire. But because they were so flat they presented almost no profile from a distance and thus were very poor targets for our artillery. I would hazard a guess that none of them was ever seriously damaged by our shellfire. The design of these posts had one major fault which enabled us to capture them. They were perfectly flat on top which meant that as a defender raised his head to look or fire he immediately became sky-lined and made a clear target for the attackers. If we kept up heavy fire they were forced to keep their heads down and that enabled us to get close. When our troops were using those same defences against the Germans in Tobruk some months later, they scattered sand bags in front and behind their positions and thus broke up the skyline which enabled them to watch and fire without becoming a target. The cover behind needed to be higher than the ground in front of anyone firing.

There were about 43,000 prisoners taken at Bardia as well as an enormous amount of equipment destroyed or captured. The food and vehicles salvaged were of immense value to our forces. I can't imagine how we could have coped without it. Their trucks were mostly heavy diesel and much superior to our poor old Chevvy utilities. The food seized was mostly pasta and canned fish. So many prisoners caused quite a problem until they could be transported to Egypt for permanent control. Some were taken away by ship from Bardia, but the bulk had to walk the fifteen or so miles to Solum for shipment.