Sailing

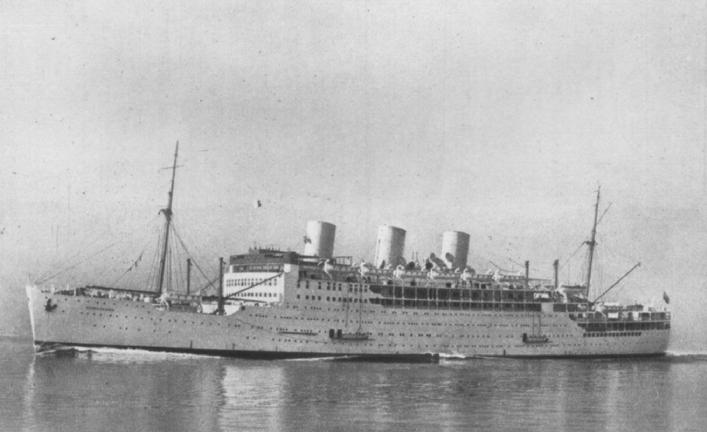

On the 3rd April, 1940, we were sent home on what was to be our Final Leave, returning to camp on the 7th. On the 15th April, we sailed from Port Melbourne in the 22,000 ton liner "Strathaird". Our departure was supposed to be a close secret but there was a large crowd to bid us farewell with the usual streamers, but lots of tears. I would not have been surprised if not all the tears were on the wharf. There were a lot of us young chaps who had never before been far from home.

Most of us were kept below until clear of the wharf then released to go on deck to wave farewell. We were all feeling pretty excited as we set off on our big adventure. Where we were going and what was likely to happen was the topic of many conversations. The most popular destination was England. Wishful thinking I guess.

We had no idea what the future held for any of us. We did not suspect that it would be over five years before most of the survivors of our battalion once again saw Australia. Most of the intervening years were spent as P.O.W.s. Many would never see their homeland again. For the moment, all that we cared about was the going. Returning was for the future and too far away to wonder about.

Once we left Port Phillip Bay and entered Bass Strait our ship started to roll. Thus we discovered that a lot of us were not very good sailors. Within a couple of days we had settled down to shipboard life and our stomachs had done likewise. All modern liners are fitted with stabilisers but not so the ships on which we were travelling. Learning that we were to sail on the "Strathaird" we thought that for once we had, to use army parlance, "Drawn the plum". All the other troops in the convoy were travelling in troop ships of about 10,000 tons while we had a luxury liner. It soon became obvious that it was to be no pleasure cruise.

The Strathhaird

Firstly we were billeted on H deck which was 8 decks down from "A" deck, below sea level with what seemed to be a thousand stairs to the top decks to parades for drill and exercise or whatever. We had no cabins, just a large deck area with tables and seats for eating etc. We learned the art, and it is an art, of getting into and sleeping in hammocks. The floor space reached the full width of the ship. On our deck there were lines of portholes with covers over them at about eye level. One of the lads unscrewed a cover to reveal that we were actually at water level. As the waves passed along the side of the ship we used to alternate between seeing the sky and being under water. We couldInt help worry a little at times about just what a terrible mess it would be if a torpedo was to hit. There would not be much chance to get out.

Then we found, because it was a luxury liner we had with us, Corps Headquarters, Sixth Division Headquarters and 17th Brigade Headquarters. Also on board was the 2/1st Australian General Hospital complete with doctors and nurses. So I presume there was General Ivan Mackay, Brigadier Stan Savige and numerous Colonels, Majors and Captains all having a say in what we could do, what we could not do and where we could go. To ensure that their orders were carried out, sentries were posted all over the place above and below decks. Any passage leading to the nurses quarters also had sentries on guard. As the only combatant unit on board, the good old 2/7th had to supply all duty personnel.

Because someone unauthorised was seen to enter the linen store deep in the bowels of the ship, a piquet of three men and a corporal was on duty there at all times. I was on duty with Corporal Bert Philp when an unexpected Ship's Inspection caught us sitting talking. After voicing strong disapproval at our slackness they left, only Regimental Sergeant Major Sutton waited behind to give us an extra blast. Corporal Philp nearly lost his stripes when he remarked that he understood that the first place a terrorist or a saboteur would head for would be the linen store, anyhow why not lock the darn door. Amazingly this is just what they did, locked it. It seems that the order, for all doors on the ship to be kept open while the ship was at sea had been mistakenly applied to the linen store. The reason for all doors to be kept open was to prevent a possible explosion jamming them and trapping people inside the cabins and saloons.

It was amazing just how big that ship was. I was part of a detail sent to roll several barrels of beer from a store at the stern to the canteen in the bows. With a barrel each we rolled along for ages with the ship rolling and plunging. At one moment one had to hold on to stop the barrel escaping, the next take care not to get run over as it tried to return aft. The passage seemed to go on forever or as one chap expressed it, "I'm sure we will have to start swimming soon, surely we left the ship some distance back". The ship was divided into about five sections by waterproof bulkheads. Movement between sections meant a climb to a higher level then a trip down to where you wished to go. To move stores as in the case of the beer barrels the bulk head doors were opened for a brief period.

The "Strathaird" was built for the Atlantic run between America and England. Thus it was comfortable in the cooler climes but once we reached the tropics it was really uncomfortable down below decks. At night with everyone trying to sleep, the heat and humidity were almost unbearable. There were long canvas tubes about three feet in diameter with a scoop at the top which reached right down to our deck via the hatchways. These brought in a steady breeze of fresh air but with the large area plus the number of bodies they did not help much unless one was within a few feet of the end.

To get some sleep a lot of us would take our blankets and sneak up onto the open deck as soon as "lights out" was sounded. Lights out only applied to below decks. No lights of any sort were ever allowed on the open decks during the trip. Smoking was strictly forbidden. We could get a good sleep on deck but had to be quick to get out of the way once daylight came as the first activity each morning was the Lascar seamen running around with hoses washing the decks, They thought it a great joke to catch someone asleep and give him a squirt of sait water. They called out "washy deck" as they went, often to a string of abuse from their wet victims. Having no right to be there we could not complain to anyone in authority, a fact that the Lascars well knew. They were very experienced sailors.

There were sports days and other activities to keep us occupied. Even long distance running was possible as seven times round the promenade deck was one mile. Most days began with a roll call parade followed by half an hour of P.T. (physical training).

The convoy called into Fremantle and we were given day leave while some Western Australian troops came on board. Supplies for the long journey were also loaded. I took the opportunity to go to Perth to see my Uncle Phil and Aunty Kath Belton and their daughters, Beverley and Wendy, none of whom I had previously met. Uncle Phil was my mother's brother and obviously the one after whom I was named. It was after dark when we sailed out of Fremantle and reformed our convoy. We were picked up by the escorting warships which stayed with us for the rest of the trip.

We next called at Colombo, again received one day's leave which was, for most of us, our first visit to a foreign country. Our ship anchored out in the harbour and we were taken ashore by launch. Bert Philp and I were invited by one of our section to accompany him ashore as he had a letter of introduction to a chap working for some public relations firm in Colombo. Our friend wanted some companions that he could trust to behave appropriately towards a coloured gent. The friend to whom the letter was addressed turned out to be a native of the city. He showed us some places we would never have found had we been left to our own resources. He was a most polite gentleman who spoke English with a lovely Ceylonese accent. He helped keep most of the hundreds of beggars and hawkers away but pointed out that he had to be reasonably polite to all these people. He had to spend his life in Colombo and it was a bad policy to make enemies. We visited a native bazaar and other places but really only touched the surface as our time was limited. We were back on the ship before dark.

From Colombo we sailed to Aden where the "Strathaird" was refuelled with coal. No leave this time but it was interesting to see the coal coming aboard in small baskets carried by natives walking up one ramp, tossing the coal through an opening in the side of the ship and then filing down again via another ramp. This went on nearly all day. We didn't feel put out by not getting ashore as from what we could see from the ship, Aden was a most uninteresting little place. Its main claim to importance was as a refuelling stop for shipping moving through the Suez Canal and into the Indian Ocean.

From Aden we proceeded to the Red Sea and along it to the Suez Canal. From Fremantle to Aden our convoy consisted of our ship the "Strathaird" and the troopships "Etric", "Nevasia", "Neuralia" and "Dunera". We were escorted by different warships at different sections of the trip but always had several on duty. They included the Battleship "Ramilles", the heavy cruisers "Kent" and "Liverpool", three Australian cruisers, "Sydney", "Hobart" and "Adelaide" and a French cruiser the "Suffren" with three smaller warships who's names I did not get. They were two destroyers and a sloop. The "Dunera" later reached England and took a load of Italian and German internees to Australia. A movie "The Dunera Boys" was recently made about the journey.

The troop carriers proceeded independently as there was now considered to be no risk of enemy attack and our arrival needed to be spaced out because there was no room for more than one ship at the time to tie up within the Canal. Ships had to unload quickly then move on. It would have been impossible to get enough trains to transport all the troops to Palestine had all four ships unloaded at the one time. We sailed along the Canal until we reached El Kantara where we disembarked on the 18th May 1940. We had now ended our first journey in a troopship. We had become so accustomed to life at sea that after nearly five weeks most of us were a little sorry to see it end. It was a clean existence and because of the limited space there was always more leisure than work.

From El Kantara we went by train to Palestine and to our camp at Beit Aria. By the time the trip was over, by reading the sign posts along the railway line, I had mastered the Arabic symbols to match our numerals. It was roasting hot when we left the train with a burning wind blowing which we were told was a Khamsin. This phenomenon occurs yearly and blows for over a month from the deserts of Egypt. Most Khamsin days are over the century mark F (38C), with the strong wind whipping up sand and dust. The Khamsin does not blow every day but approximately half the time in March and April and occasionally in May. We were fortunate to have arrived at the end of the Khamsin season.

When disembarking we were all wearing winter uniforms so were glad that there was only a very short distance to reach the camp. We were very pleased to get into shorts and shirts which were to be our usual work attire from then on. We lived under canvas with the office buildings, kitchens and ablution areas being the only permanent structures. Our camp had been occupied by various British units for many years. The Arab labourers who worked around the area cleaning gutters and such, became very friendly and said that we always treated them fairly.

The railway line formed one boundary of the camp (50 yards from my tent). On the Battalion notice board when we arrived, someone had pinned a large scorpion, with the warning "Beware of these Bastards, they bite". This scorpion was at least three inches long and the same distance between its claws. We were to meet quite a few like it while in Palestine, Egypt and Libya. One interesting feature of the railway line past the camp was the famous Orient Express travelled past a couple of times a week. It was always preceded by an armoured rail car which we were told was to explode any mines which may have been placed on the line by terrorists. As an added precaution there were usually three flat top trucks being pushed in front of the engine. The Orient Express ran from Istanbul to Cairo.

While at Beit Jirja, we received quite a lot of leave to places such as Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Jaffa, Jericho and the Dead Sea. While on one leave to Jerusalem I met a cousin of Shirley's who had sailed with one of the other battalions on one of the smaller vessels in our convoy. I was amazed to see the usually rotund Mac. Young looking slimmer than I was. He told me a sad tale. He had spent the entire trip from Australia in the ship's hospital, seasick. He swore that he would never return to Australia if he had to go by sea. Just how he fared on the home journey I don't know.

During our stay in Palestine my platoon was rostered to spend a week guarding a food dump some distance north of our area. It was a huge building, about a hundred yards long, with a rail line along the front. We were told that it held sufficient rations for ten thousand men for a couple of months. We were not there long before we discovered that previous guards had made a gap in the wire and had been helping themselves to Australian preserved fruit. We were soon doing the same thing. An inspection by the controllers found the hole and called a Court of Inquiry. They wasted their time as so many different units had been involved in guarding the dump since their previous inspection. Any one of those units could have made the hole and stolen the stores.

One of our members was a chap who was about six feet two tall (188 MM) and heavily built with a brain in reverse proportion. When we heard of the inquiry we were in a panic until we found that Turk McGlurk, as he was known, was feeling off colour so arranged for him to be rushed off to hospital on the day that mattered. He would certainly have spilled the beans under close questioning. Some of the boys used to pull his leg a bit but all he would drawl was "You talk too much". While he was in the hospital it was realised that he really was unfit to be an infantry man. They kept him as a handyman around the place especially useful for cutting firewood. Some three years later in New Guinea I drove a sick man to our hospital near Dobadura and there behind the hospital I met good old Turk. He and I were always friends as I thought it a bit unfair to tease him and never did so. We greeted each other warmly and when I asked him what he was doing in N.G. he replied "Still cutting bloody firewood".

Another duty some of us did was guarding the pumping station that supplied our camp with water. Some of the Arab groups were getting restless and for a while it was feared that they would blow up a few of the pumping plants in the area. Even then the Arabs resented the influx of Jews into Palestine. I guess they could not be blamed for that. Apart from our pumping plant there were several others run by Jews to irrigate their orchards and gardens. The pumps were driven by big diesel engines that we could hear thumping away day and night.

That part of Palestine was amazing. It appeared to be all sand but just add a little water and fertiliser and the desert fairly bloomed. The Arabs mostly planted a few watermelons and grapes along water courses, planted millet on the less sandy patches then left it up to Allah to do the rest. The Jews planted those crops, also other things plus a hedge for a wind break. After installing irrigation they produced in a big way, grapes, oranges, grapefruit, watermelons and fruit trees of various types. The under-ground water that everyone was drawing on was said to be from the Mediterranean some three miles away. It took over a hundred years to travel that far through the packed sand and on the way had lost its salt. At least I think that it had lost most of the salt. It didn't taste all that sweet and was not good for washing clothes.

This fertile sandy strip was only a few miles wide and ran mostly from Gaza to Tel Aviv. The rest of the country varied widely. Where we often trained further inland, we soon found ourselves on wind and water eroded hills that grew nothing. High ridges carved with wadis which varied between four and twenty feet deep. We spent a lot of time sneaking up on imaginary enemies or defending ourselves along them. This was where our Company 2nd In Command earned the name of Wadi Mac. The name stuck to him right through until his capture.

The Beit Jirja camp was run by bugle calls. We awoke to the reveille, with it's "get out of bed you lazy loafers" went to eat by "come to the cook house door boys", went on parade to "fall in A, fall in B, fall in every company", stood to attention at 1800 hours to the "Last Post" and turned in on the call of "lights out" at 2200 hours (10 pm). There were other calls to learn such as "Officers report" and "Turn out the guard". There were a couple of others that I have forgotten. Fitting words to the calls enabled one to more easily remember which call meant what. Naturally some of the words were not fit to print. The Battalion was scattered over a wide area and the bugle was the best means of getting the messages out to all corners.

I went on leave to Jerusalem on three occasions staying over night at the hostel provided for Australian forces. A big advantage in this for both the soldier and the army lay in the fact that we were able to get the type of food to which we were accustomed. This prevented us falling foul to the various stomach complaints which one could so easily catch eating foreign foods. I have decided to not spend time writing about Jerusalem as I am sure I could not add to what experts have already written many times.

We normally would enter the Old City of Jerusalem via the Davids Gate. On both sides of the gate it was flat but a few yards inside the gate the slope began and many of the streets then consisted of steps. The little donkeys trotted up and down the steps in an agile manner but we two-legged donkeys, wearing army boots with steel plates on heel and toe, spent half our time scrambling to avoid falling flat on our backs. Those stone steps had been in use for a few thousand years and were worn round and slippery. The citizens with bare feet or soft sandals had no trouble negotiating them. I was able to visit the various religious sites which claimed to be where Christ was crucified and placed in the tomb but as there was more than one of each I was left a little confused. Now I would know the truth.

Jerusalem is built atop a very high mountain. The climb up was winding, steep and hazardous. In one place there were seven consecutive bends, each so sharp that the buses had to back off to enable them to get around. This, on a slope so steep that they were in low gear most of the time. I have heard that a few years ago a new road was opened eliminating that section. The hillsides were very stony and steep but the sheep and goats seemed able to find enough to eat. The sheep were the strange looking (to Aussie eyes) fat tailed sheep. They have existed unchanged for centuries.

From Jerusalem we went by bus to Jericho and the Dead Sea. That was a long downhill run. On the side of the road in one place was a sign saying that this was sea level. We had already descended about two thousand five hundred feet and still had thirteen hundred feet to descend. Some of the boys went for a swim in the sea just for the sake of doing so but it was too cold for me. It was strange to see people head and shoulders out of the water if they floated upright. Because of the salt content the Dead Sea is so buoyant that it is impossible for a body to sink. It has about ten times the salt content of the normal oceans. Jericho was interesting and well worth a longer visit.

We occasionally did what was called "waving the flag". This entailed usually a Platoon of about 30 men, travelling in trucks, dressed in battle dress and heavily armed calling at various Arab villages and paying a courtesy call on the Village Chief or Mukhtar. While the officer took coffee we took up defensive positions nearby. The officer was welcome to the coffee. At one village the chief came out and gave us a cup full each. Talk about poison, strong and black without sugar. We were glad the cups were only about thimble size. We didn't know whether or not we frightened anyone but at least the Arabs never gave any trouble.

On one manoeuvre by transport, the ones we liked the best, we reached the Jordan River. We found that the bridge over the river had collapsed owing to terrorists having placed a bomb under it some time before. There were guards on the opposite bank and they permitted us to cross over the wreckage of the bridge so that we could say that we had visited Jordan. The structure was known as the Allenby Bridge, named after the Australian General who led the campaign in Palestine against the Turks during World War 1. The longest such trip was to Beersheba. It is one of the oldest towns in the world to be continuously occupied. We spent some time sight-seeing. We also saw the well that was said to have been dug by Abraham. People still draw water from it to this day. The area surrounding the well has slabs of rock showing above the ground. Because of all the traffic for so many centuries the rocks are polished to a mirror finish. The story that Abraham dug the well is probably true because the Bible records that he dug several wells during his moves around Palestine. Jacob lived in Beersheba for some time and it was from there that he journeyed to Egypt. Abraham's wife Sarah is thought to have given birth to Isaac in Beersheba.

On the way back to camp we stopped at the site of the famous charge by the Australian Light Horse against the Turks during World War One. The Turkish trenches were still plain to be seen on the ridges. In that charge 800 Australian horsemen routed 2500 Turks in the last great Cavalry charge in modern warfare. This charge may not be quite as well known as The Charge of The Light Brigade at Crimea but was a lot more successful. The necessity to obtain the Beersheba water for their horses lay behind the decision to capture the town. The Australians were not cavalry but light horse which meant that they were basically mounted infantry.

While we were at Beit Jirja word filtered around that an Arab had set up a "house of ill-repute" not very far from the camp. The Army heard about it and placed the area out of bounds to all troops. To further make the area safe they asked battalions in the area if they could supply a picket, preferably of eunuchs if any available. As none appeared to be available the Palestine Police moved in and shifted the occupants of the house out of our area.

A few weeks after our arrival in Palestine we suffered our first loss when a member of my section fell ill with what seemed to be just a bad case of the flu. He was sent to hospital. A week later we were shocked to hear that he had died of some strange virus. His name was Jack Reynolds, a man in his thirties about six feet tall and strongly built, not the type we would have expected to fall victim to any disease. He had told us of losing his older brother in the first war and felt that he could not wait to have a go at the Germans to avenge his brother's death. But fate decreed otherwise. Jack did not get his wish.

The funeral date was arranged and six members of his section, which included myself, were detailed to be coffin bearers. It was to be a full Military Funeral with 2/7th Battalion Band, a Firing Party, Guard of Honour and was to take place at the Australian War Cemetery at Gaza. We picked up the coffin containing his body from the hospital, proceeded to the cemetery where we found the band waiting some distance outside the gates of the cemetery. We were a bit apprehensive when we saw the distance of the carry as Jack was a very heavy man plus the coffin of heavy wood.

We were even more worried when the band started to move off in front of us, as right from the start they played slow march time. We "slow marched" along the road, turned into the cemetery to find the entire Company drawn up as a Guard of Honour reaching to the far end of the cemetery. The laneway between the graves was up hill all the way. The two of us who had the heaviest end were ready to drop by the time we arrived at the grave-side as the two chaps in the middle were too short to take their full share of the load. However once it was over we were glad that we had been able to do it as a mark of respect for our friend.

General Sir Thomas Blamey had his Headquarters in Gaza. I spent a week with my platoon guarding his house and the beautiful gardens surrounding it. There was some criticism of our General Officer Commanding for being the only man in the A.I.F. to have his wife in the Middle East. I guess that was a perk of office. Lady Blamey was also entitled to be there in her position as Australian Commander of the Red Cross. During off duty periods we were able to take a stroll around the streets of Gaza and have a drink with some of the Arabs. We raised the point with them of some Arabs not drinking alcohol. They explained that it was only among the extreme Islamics it was forbidden. Drinking was alright, it was getting intoxicated that was a sin.

One problem that annoyed our chaps was the fact of having to use tin cups from which to drink their beer. Anyone who has been forced to take their beer warm from a tin mug will understand. After a near riot an answer was found. The Army Engineers cut beer bottles in half and used the base halves as drinking glasses. As the idea was said to come from the lady, these glasses were known as "Lady Blameys".

I was fortunate in getting an extra visit to Jaffa which was usually out of bounds to Aussie troops. I was one of two men selected as a picket to accompany some English provosts in patrolling the town to remove any Australian troops in Jaffa. An army picket is normally a lightly armed soldier on law and order patrol. We wore only our bayonets. Apart from our uniforms of course. I found it quite interesting to have an escort through the seamy parts of a seedy town. We visited several brothels, were surprised to find that some of them were cleaner and tidier than some of the hostels where we stayed. Jaffa is an extremely old city mentioned in the Bible as being old then. Tel Aviv joins onto the northern side of Jaffa. Tel Aviv is one of the worlds youngest cities.

While we were in the area the ship on which the Jews escaped from Europe was still aground just off the main beach. When the British authorities refused it permission to land its passengers, the crew overcame the problem by "accidently" running the ship ashore. The shipwrecked passengers could not then be refused shelter on land. Because it was being used as an aiming mark by bombers trying to hit Tel Aviv the authorities started to blow it up. On the day that I was there a massive explosion blew much of it away. One person about 400 yards away was struck and badly injured by a piece of flying steel.

After about three hours in Jaffa we all returned to the Provost Headquarters in Tel Aviv where we were given leave passes and told to take the rest of the day off so long as we returned to camp before lights out. We hired a couple of surf boards, paddled along the water front but were turned back when we attempted to approach the ship.

During these visits to Tel Aviv we often met groups of Polish soldiers. There was a Free Polish Brigade camped nearby, also there were a lot of Polish Jew civilians in Tel Aviv. These Polish soldiers had escaped when their country was overrun by the Germans in 1939. Having made their way to the Middle East they were formed into a unit with its own officers. They fought on several fronts including in the siege of Tobruk. Because of their hatred of everything German they fought fiercely and bravely. I enjoyed talking with them as several spoke very good English. I was always surprised to note that whenever I met groups of people from other countries there were always some who spoke English. We, because of our country's isolation had very few bilingual members and were often disadvantaged by this, especially when shopping.

There was an event which occurred annually in Palestine that I was privileged to see. Each year millions of quails migrate from Europe to Africa, crossing the Mediterranean Sea and reaching land for a rest near and south of Gaza. The young Arabs had strung nets on poles along the first row of sand dunes. When I saw them they were catching hundreds of the birds. They would have made first class eating.

At last, after five months, it was time to move to Egypt, part of B Company being chosen for the rearguard. This entailed pulling down tents, folding them, storing them in a safe place and, of course, guarding everything. The main body of the battalion left for Egypt on 19th September. We said goodbye to the Arab workers in the camp. One chap said, he hoped that no English soldiers would be taking our place. It seems the Poms treated them as inferiors and if they got in the way would kick their tails. As he expressed it, "English soldiers, many times hitting and kicking, Aussie soldiers, five months, no hitting, no kicking". Most of the older Arabs fondly remembered the old Diggers from the first war. These earlier soldiers would have been the Light Horse.

There was an Arab village less than half a mile away on the opposite other side of the railway line from the camp. The young Arabs were very interested in our activities and, if we took our eyes off things for a few minutes, they would steal something. Our canteen had been burnt down a few days before the departure of the main body of troops, oddly enough just as they were starting a stocktake and audit. We were not able to clear away the mess and get rid of it as the Insurance Company wanted it left for examination.

Young Arabs used to sneak in, sometimes at night, grab anything they could reach and run like mad. They were too fast for us. The main trouble was that most of the things they grabbed were of no use to them. They would toss them away and return for another lot. Soon the area outside the camp was a mess of tins and bottles. We stopped it by trapping one lad about fifteen years old and putting him on a mock trial at which he was found guilty of stealing military property and sentenced to death by firing squad. To us it was a mock trial but to that lad it was deadly serious. The poor kid was nearly fainting when an eloquent plea from the interpreter persuaded our officer to forgive him this once. We had no more trouble from the kids of that village.

When the call came for the move to Egypt, Lt.Colonel Walker was on a four days leave to Tel Aviv. It was on the second day of his leave that he was recalled to camp. Because he was a rather mild looking fellow with a high voice and a delicate way of standing he was soon given by the ranked, the nickname of "Myrtle". When he arrived back in camp it was dark and as he approached the officers compound he was challenged by the sentry. In reply to the "Halt who goes there", he replied "Commanding Officer Colonel Walker". Thereupon the sentry replied "Cut out the bull, Myrtle is on leave". That put a "cat among the pigeons" with officers and others all in trouble. It is just as well I was not on duty that night as I would probably have replied in similar vein.

There were some hilarious moments following the burning of the canteen. During the fire itself there was a lot of confusion due to the lack of water. For a time it appeared that the whole camp would burn as a strong wind was blowing and the tents were fairly close. These were saved by pulling the pegs, allowing them to fall flat on the ground and posting men with buckets of water on each tent. After the fire was out the biggest heap remaining was the recently arrived beer supplies delivered packed individually in straw sleeves, in wooden crates. These now consisted of a black pile of straw, broken glass and half-burnt boards.

A guard was put on the debris to keep away the inquisitive. About 9 o'clock at night Corporal Philp was told to choose four reliable men, preferably non-drinkers, and report to the guard tent. We arrived to find half the canteen guard were drunk and unfit for duty. It appeared that someone had discovered the beer in the centre of the heap was unharmed thus each shift of guards came on duty sober but by the end of two hours was capable of little more than sleeping. Our job was to guard the guard to ensure that they could not get at the alcohol again. Anticipating this, some of the boys had hidden supplies around the camp. Some people wandered about in a daze for a couple of days.